Jedinečný zážitek v jednom z nejkrásnějších pozdně renesančních paláců Prahy.

Martinický palác na Hradčanském náměstí, v těsné blízkosti Pražského Hradu s působivou historií a jedinečným interiérem dodá každé události neopakovatelnou atmosféru. Pronajmout si můžete prostory k pořádání společenských akcí, rautů, koncertů, konferencí, výstav a veletrhů, přednášek i svateb.

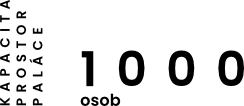

Nabízíme pronájem jednotlivých pater i celého paláce.

K dispozici je parkování ve dvoře a free wifi.

created by Need4web s.r.o.